If you’ve ever seen the movie Momento, so much of the story-telling lies in how they order the story. It all feels jumbled until you realize the ordering is intentional. Interestingly, you can find an “unofficial” cut of the movie where the whole story is re-edited in chronological order. You’re still told the same content by watching it chronologically, but it certainly hits differently.

The same can be said when structuring the Hebrew vs. the Christian order of the Old Testament.

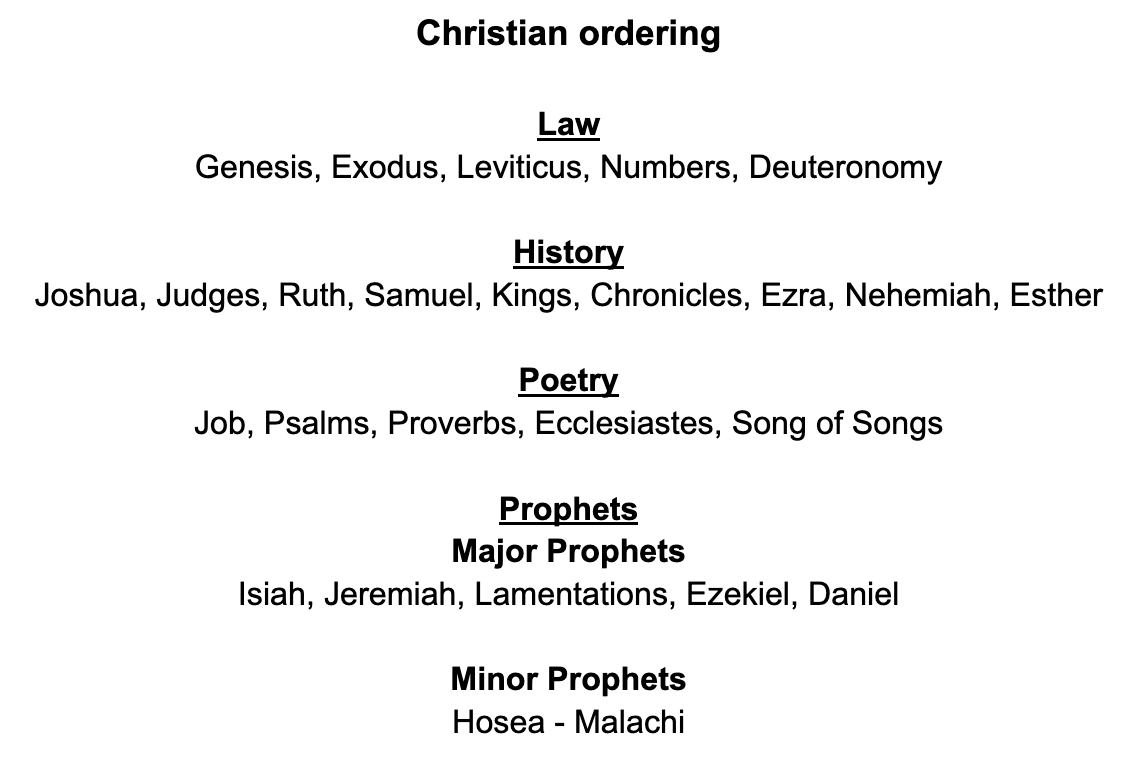

As mentioned in our latest podcast episode, this difference occurred during the formation of the Septuagint translation (typically abbreviated as LXX) when the Old Testament was translated into Greek. In the process, the three-fold structure of the Hebrew Bible (Torah-Naviim-Ketuviim, also known as the TaNaK) would instead be “re-edited” into a four-fold structure that catered more towards genre - Law, History, Poetry, and Prophets. (See the charts below).*

To add to the complexity, the New Testament authors who wrote in Greek regularly cited from the Septuagint since Greek was the dominant language of the day. (For more on this, see Richard B. Hays’s Echoes of Scripture in the Gospels and Echoes of Scripture in the Letters of Paul.)

So, which is the better way to study the Old Testament? Well, it depends.

By reading according to the Hebrew order, we’re able to see the macro-story of the Old Testament more. The Torah sets up God’s people and promised land. The Naviim (Prophets) sets up how God’s people lived in the Promised Land and eventually were exiled. The Ketuviim (Writings) speaks primarily about how to live in exile and trust in God’s promises. (For more on how to interpret the Hebrew ordering, see Stephen Dempster’s Dominion and Dynasty: A Theology of the Hebrew Bible.) It also seems Jesus and the apostles affirm the Hebrew ordering with the oft-repeated phrase “Law and the Prophets” (Matthew 7:12; 11:13; 22:40; Luke 16:15, John 1:45, Acts 13:15; 24:14, 28:23, Romans 3:21).

By reading according to the Christian order, we can read more clearly from genre to genre. The New Testament authors seem to endorse this ordering, albeit implicitly, when they use word-for-word phrases from the Septuagint.

So which way is better? Well, the good news is we don’t have to pick sides. Both orderings are helpful and provide fresh ways to understand and appreciate the Old Testament. Not to mention - it’s a story worth re-reading over and over again!

These orders are from Chronological and Background Charts of the Old Testament by John H. Walton, p.12

*Note: There is some discrepancy in both the Hebrew and Christian ordering of the Writings.